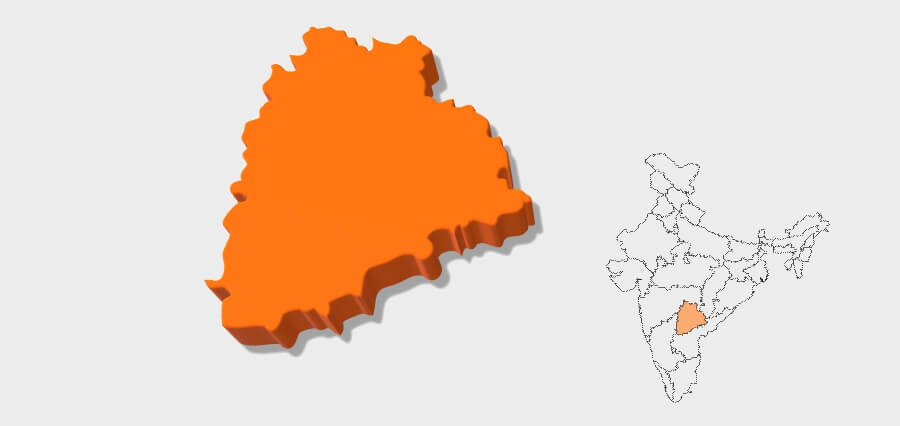

The issue arose during the court’s consideration of an appeal brought forth by Mohd Abdul Samad, who was directed by a family court in Telangana to provide Rs 20,000 monthly maintenance to his former spouse. The Supreme Court, while deliberating on the matter, noted that the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act of 1986, enacted in response to the Shah Bano case verdict during the Rajiv Gandhi administration, does not explicitly prohibit divorced Muslim women from filing a petition under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) of 1973 to seek maintenance from their former husbands. The court, chaired by Justice B V Nagarathna and comprising a two-judge bench, pointed out that the Act does not contain provisions explicitly disallowing Muslim women from filing petitions under Section 125. The justices questioned whether they could impose such restrictions on the Act in the absence of explicit language to that effect.

The issue arose when the court was handling an appeal from Mohd Abdul Samad, who had been instructed by a family court in Telangana to provide Rs 20,000 in monthly maintenance to his former wife. The woman had approached the family court under Section 125 of the CrPC, alleging that Samad had pronounced triple talaq. Samad appealed to the High Court, which, while disposing of the plea on December 13, 2023, acknowledged that “several questions are raised that need to be adjudicated” but “directed the petitioner to pay Rs 10,000 as interim maintenance.”

Disputing this decision, Samad informed the Supreme Court that the High Court had overlooked the fact that the provisions of the 1986 Act, being a Special Act, would take precedence over the provisions of Section 125 of the CrPC, which is a general Act. He argued that “the provisions of Section 3 and 4 of the” 1986 Act, which begin with a non-obstante clause, would supersede the provisions of Section 125 of the CrPC, which lacks a non-obstante clause. Thus, he contended that the application for maintenance under Section 125 of the CrPC would not be admissible before the Family Court when the Special Act grants jurisdiction to a First-class Magistrate to adjudicate matters related to Maher and other subsistence allowances under Section 3 and 4 of the 1986 Act.

On February 12, the Supreme Court had assigned senior advocate Gaurav Agarwal as the amicus curiae for the case and requested his insights. During the proceedings on Monday, Agarwal informed the bench, which also included Justice Augustine George Masih, that “in my opinion, Section 125 proceedings remain valid even after the Shah Bano case.”

He further conveyed to the bench that the issue of whether the 1986 Act nullifies the rights under Section 125 of the CrPC was not addressed by the Supreme Court Constitution bench in the 1986 ruling in Danial Latifi v. Union of India. “Nevertheless, the remarks in paragraph 33 of the judgment imply that the 1986 Act should be interpreted in a manner that ensures divorced Muslim women are entitled to the same maintenance rights as other divorced women in the country. Thus, the rights of divorced women cannot be selectively revoked for a specific group, as it would violate Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Constitution. Therefore, the validity of the 1986 Act was upheld under the understanding that it does not discriminate against Muslim divorced women compared to other divorced women,” he explained.

Senior Advocate S Wasim A Qadri, representing the ex-husband, argued that if Parliament intended to permit Muslim women to file petitions under Section 125 of the CrPC, the enactment of the 1986 Act would have been unnecessary.